Tasks in JAMScript Programs

A JAMScript program has C and JavaScript functions with some of them prepended with the jasync or jsync keywords. In this section, we refer to such tagged functions as JAMScript tasks. A task is considered local if it runs in the same node as the invoking function while the tasks running in a different node are considered remote. A JAMScript task runs in a single node; that is, a given task is not distributed across multiple nodes.

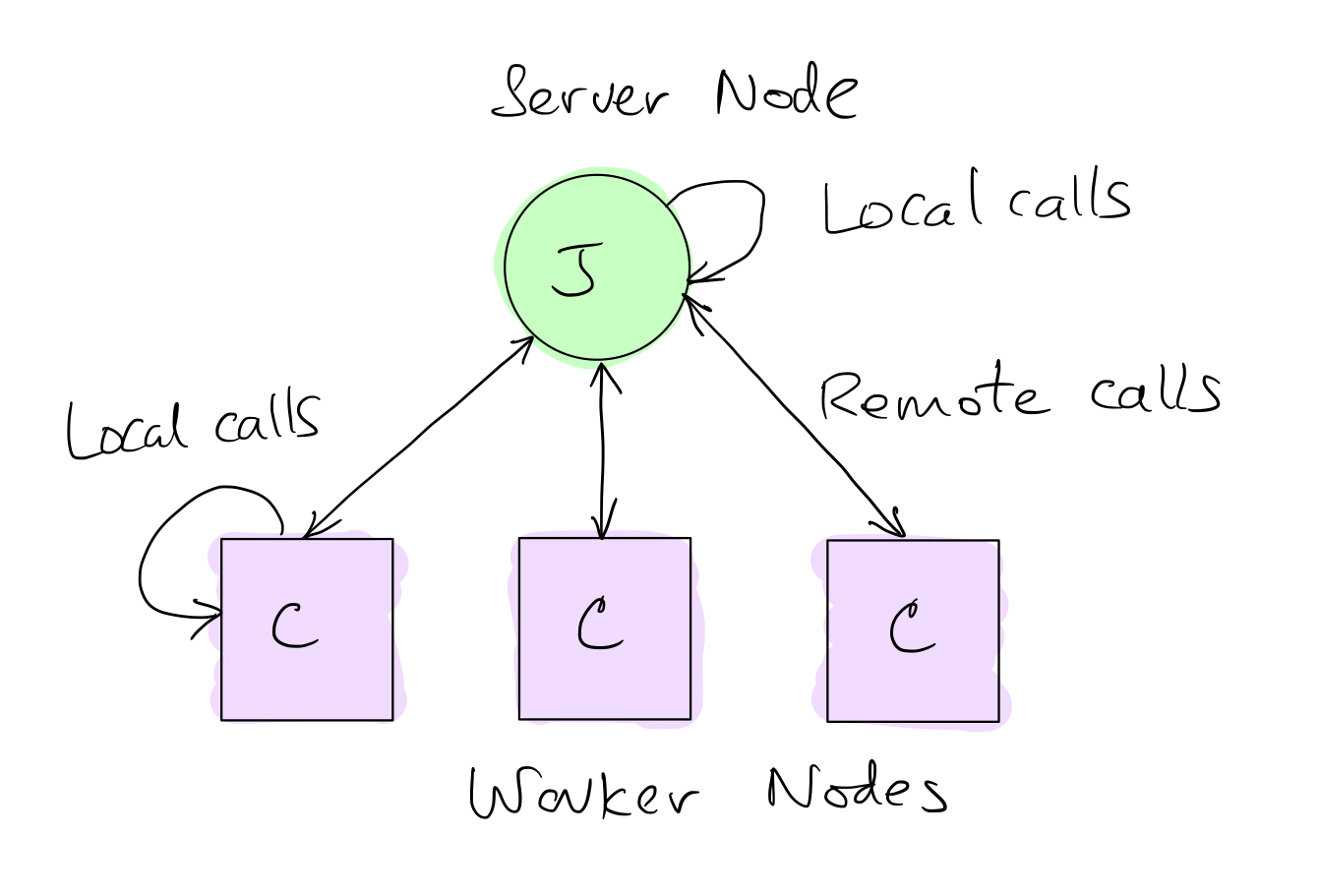

We have local tasks in the worker (C) side as well as the controller (J) side. The remote tasks are in between C and J nodes. For the time being, we will ignore multiple (hierarchically organized) controllers. The C nodes can invoke remote tasks only on J nodes. Similarly, J nodes can invoke remote tasks on C nodes. A simple configuration with one J node and three C nodes is shown in the figure below.

Defining and Using Local Tasks

Local tasks can be defined at the worker and controller sides. Here, we illustrate the definition of local tasks in the C side. Consider the following C side program.

jasync localme(int c, char *s)

{

while(1)

{

jsleep(20);

printf("Message from me: %d, %s\n", c, s);

}

}

jasync localyou(int c, char *s)

{

while(1)

{

jsleep(100);

printf("Message from you %d, %s\n", c, s);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

localme(10, "my message");

localyou(100, "your message");

}

You will notice that all the calls made by the C program are local. Therefore,

this worker (C) program can run with a NULL controller (empty J program). The

local tasks are invoked just like any other function. However, because the local

tasks are asynchronous (defined using the jasync keyword), there is no return

value from them. In this example, the localme and localyou tasks run

concurrently. For compute only tasks, you need insert jsleep(n) to yield the

coroutine thread; otherwise, you would not have the intended execution.

You can save the above

code under a file with a .c extension (local.c) and create another empty file .js extension (local.js).

To create the executable, you run the following command.

djam compile local.c local.js

This should create local.jxe as the output. You can run the JAMScript executable local.jxe as follows:

djam run local.jxe

To view the output of the program (in this case from the C side), run the following command.

djam term

The primary use case for local tasks is to perform concurrent processing at the worker. All local tasks and the main program run on a single kernel-level thread because JAMScript is a single-threaded language like JavaScript.

The above example shows how to multiplex two task that print messages to the terminal. In addition, we can also have local tasks that read data from the controller as illustrated in an example shown later.

Defining and Using Remote Tasks

Remote tasks are important for the controllers and workers to interoperate. Lets consider a slight variation of the

above program with two local tasks in the worker. In the program below, we just have one of the tasks localme.

However, instead of calling that task locally, we call it from the controller.

jasync localme(int c, char *s)

{

while(1)

{

jsleep(20);

printf("Message for me: %d, %s\n", c, s);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

printf("Not calling any local tasks \n");

}

The J node runs the very simple program shown below.

var count = 10;

setInterval(function() {

localme(count, "message from J");

count++;

}, 10000);

In the above program, the J node is calling localme as a remote task. You can see that the J node spawns a different

instance of the localme at each call, which runs forever. Therefore, we will run out of the resources at the devices

after few invocations.

Typically, the remote tasks run to completion within a given duration so the resource usage at the worker side would not keep increasing like in the above example.

In the above example, the controller was calling a remote task in the worker. We can call a remote task in the controller from the worker as well. In the code fragment shown below, we export a J function so that it can be called from the C node.

jasync function printMsg(msg) {

console.log("This is a message from C" + msg);

}

In the C side, the function exported from the J side needs a prototype definition so that it can be used there.

void printMsg();

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

printMsg("Hello, Controller");

}

A controller can have many workers underneath it. Therefore, when a controller

issues a remote asynchronous task execution request (like the localme request

in the above example), all workers underneath the controller will execute the

task. However, when a worker invokes a task on the controller, the task runs in

the controller that is attached to the worker (like printMsg running in the

controller).

Synchronous Tasks and Return Values

Asynchronous tasks are fired and forgotten by the caller. With the synchronous tasks, the caller waits for the completion and the ensuing return result. The calculator example from the Quick Start section is an example use of synchronous tasks. The listing below shows the calculator server.

jsync function add(num1, num2) {

return num1 + num2;

}

jsync function subtract(num1, num2) {

return num1 - num2;

}

jsync function multiply(num1, num2) {

return num1 * num2;

}

jsync function divide(num1, num2) {

return num1 / num2;

}

The functions that perform the calculator functions such as add, subtract, multiply, and divide are defined

as synchronous tasks.

The C side shown below calls the synchronous tasks to perform the required calculations. The C call blocks until the task is complete and a result is available from the task. The function prototype (required) in the C side defines the return type of the task.

#include <stdio.h>

// Prototypes for the functions exported from the J side

int add(int, int);

int subtract(int, int);

int multiply(int, int);

int divide(int, int);

int main() {

char operator;

int num1, num2;

while(1) {

printf("Enter an operator (+, -, *, /) or q to quit:");

scanf("%c", &operator);

if(operator == 'q' ) {

exit(0);

}

printf("Enter the first integer operand: ");

scanf("%i", &num1);

printf("Enter the second integer operand: ");

scanf("%i", &num2);

switch(operator) {

case '+':

printf("%i + %i = %i\n", num1, num2, add(num1, num2));

break;

case '-':

printf("%i - %i = %i\n", num1, num2, subtract(num1, num2));

break;

case '*':

printf("%i * %i = %i\n", num1, num2, multiply(num1, num2));

break;

case '/':

printf("%i / %i = %i\n", num1, num2, divide(num1, num2));

break;

// operator doesn't match any case constant (+, -, *, /)

default:

printf("Error! operator is not correct\n");

}

//Lazy input clear

int c;

while ((c = getchar()) != '\n' && c != EOF) {}

}

return 0;

}

In the above program, worker (C) is calling synchronous tasks provided by the controller (J). A call from the worker leads to a single execution because a worker connects to a single controller. Now consider the reverse situation where the worker is hosting the synchronous task. There could be many workers underneath a controller. So when the controller calls the synchronous task, we have many concurrent runs at the different workers. The controller needs to wait for the completion of all task runs and return an array of all the results. To collect all the results, we need to have all the tasks completing around the same time. The task runs at the different workers can take different times due to processor or data differences. Therefore, the only constraint JAMScript makes is to start all the runs at the same time across all the workers.

Here is an example program with both controller (J) to worker (C) and worker (C)

to controller (J) synchronous task calls. The C program shown below has one

local task (trygetid) that calls a synchronous remote task (getID) to get an

identifier from the controller, which is stored in a local variable called

myid. The synchronous remote task hosted by the worker (tellid) returns this

identifier upon invocation.

int getID();

int myid = -1;

jasync trygetid()

{

while(1)

{

jsleep(1000);

myid = getID();

printf("MyID %d\n", myid);

}

}

jsync int tellid()

{

return myid;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

trygetid();

}

The J program is shown below. It implements the synchronous remote task

getID, which the workers call to get their identifiers. Periodically, the

controller is calling the synchronous task tellid to get the list of workers

underneath it. Because the workers periodically refresh their identifiers by calling

getID, we should see an array of different numbers printed out by the program below.

The number of elements in the array corresponds to the number of workers underneath the

controller.

var count = 1;

jsync function getID() {

return count++;

}

var nodes;

setInterval(function() {

nodes = tellid();

if (nodes !== undefined) {

console.log(nodes);

}

}, 1000);

Chaining Asynchronous Tasks via Callbacks

The fire and forget nature of the asynchronous remote tasks is quite useful when you want to launch a task in the remote node (it could be the controller or worker) and proceed to the next statement in the program. However, in some problems it is necessary to perform another task after the asynchronous task so launched has completed or even perform a remedial action if the asynchronous task failed. For this purpose, JAMScript supports callbacks for asynchronous tasks.

Consider the following program in the C side. In this program, through a local task (trycallback) we

are calling remote task printMsg. The call, however, is different from the previous ones – here we are

passing a callback as the last parameter in the call. The callback is a special type in JAMScript – jcallback.

void printMsg(char*, jcallback);

void printRet(char *s)

{

printf("Callback returned %s\n", s);

}

jasync trycallback()

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{

jsleep(500);

printMsg("hello from worker", printRet);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

trycallback();

}

The J side of the program that implements the remote task with callback support is shown below. The callback from the controller only goes to the worker that made the initial call. It does not reach other workers that are present underneath the controller. When we run the program shown here with 3 workers, 9 messages will be printed at the controller, but only 3 messages will be printed at each worker that corresponds to the calls that were made by the worker.

var mymsg = "hello from controller";

jasync function printMsg(msg, cb) {

console.log("Message from worker: " + msg);

cb(mymsg);

}

In the above example, the controller calls back the worker. It is possible to have the workers

calling back the controller as well. In this case, the controller can receive many callbacks

corresponding to each worker it has underneath it for each remote task it executes. The

example below shows workers calling back the controller. You can notice that the

remote task callworker has the last parameter as jcallback.

jasync callworker(int x, jcallback q)

{

printf("Value %d\n", x);

q("message to controller");

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

// Empty main

}

The J side (controller) is supplying a callback function (in this case poke) when it calls the remote task callworker. If you run this program with 4 workers, you will the callbacks arriving as groups of 4 at the controller (i.e., one from each worker).

function poke(msg) {

console.log(msg);

}

(function qpoll(q) {

q = q -1;

console.log("I = ", q);

callworker(10, poke);

if (q > 0)

setTimeout(qpoll, 500, q);

})(10);

Tasks at Cloud, Fog, and Device Levels

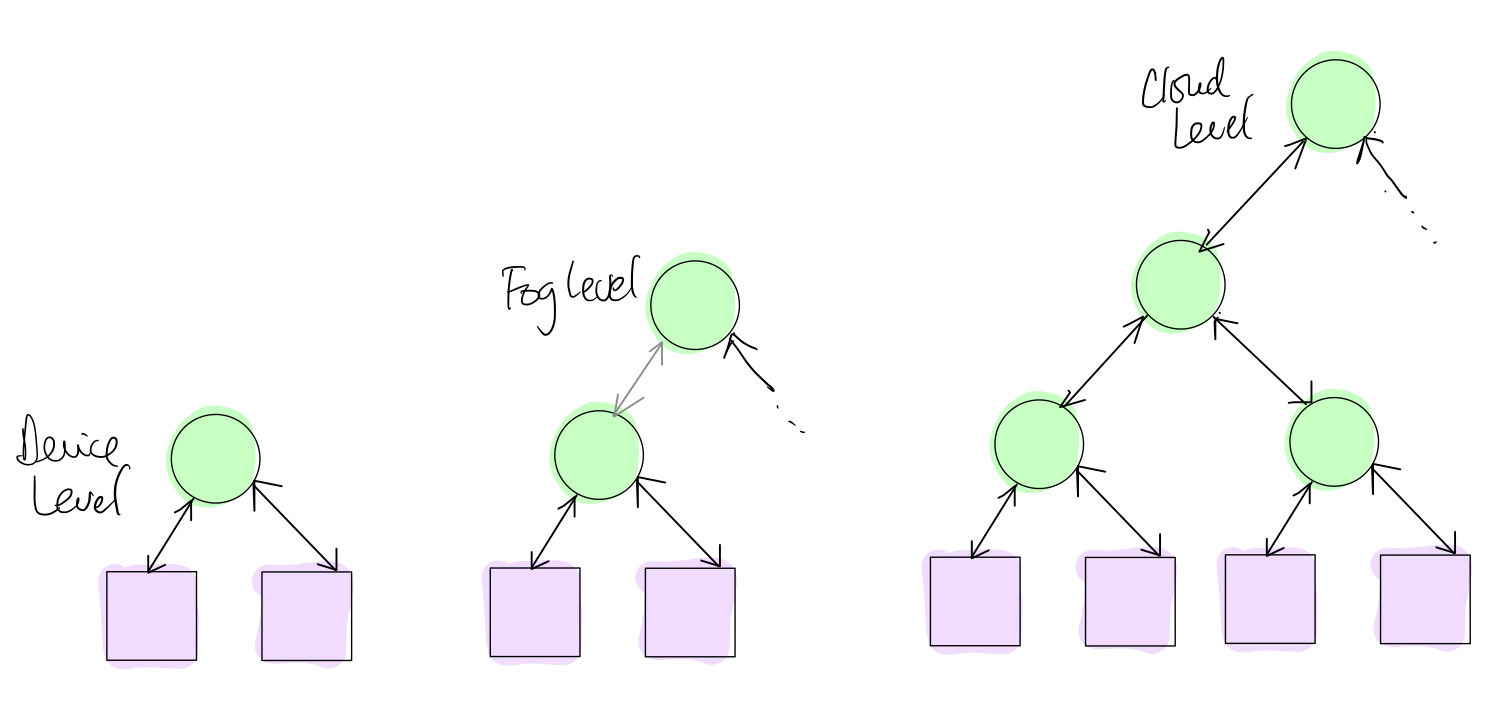

JAMScript is designed so that programs written in the language can run in a distributed collection of nodes in cloud, fog, device levels. Optimally mapping the program components into the distributed system formed by the cloud, fogs, and devices is part of ongoing research in JAMScript.

Lets consider the cloud, fog, device hierarchy. The J node can run at the cloud, fog, and device levels. The C node runs only at the device level. That is, the device level has both J and C nodes while the rest run only J nodes. The figure below shows the different deployment scenarios that are possible in JAMScript.

The JAMTools (i.e., the jamrun and djamrun commands) determine the mode of deployment

of a JAMScript executable. That is, a JAMScript executable is universally deployable in

many different forms. From inside a JAMScript program, we can determine certain parameters of the

deployment such as node type. The code shows how a J node could print out different messages based on

the level at which it runs.

if (jsys.type === "cloud")

console.log("I am running at the cloud");

else if (jsys.type === "fog")

console.log("I am running at the fog");

else if (jsys.type === "device")

console.log("I am running at the device");

else

console.log("Unable to determine the level");